| Return

to History of the Area

Scotts

Run

America's Symbol of the Great Depression

in the Coal Fields

RONALD L. LEWIS

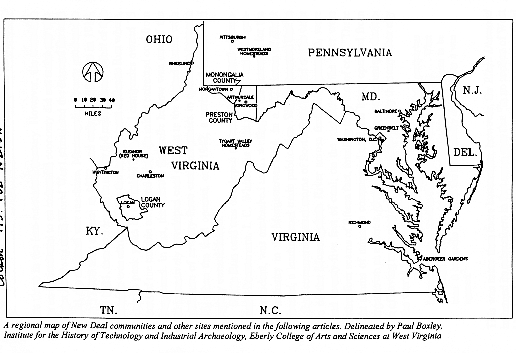

Arthurdale's

60th anniversary slogan proclaims that "The

Dream Lives On." The story of this New Deal

community is affirmative and inspiring, a tale

of triumph against the odds, the kind of story

Americans embrace. The dream of Arthurdale was

born out of the chronic despair that First Lady

Eleanor Roosevelt found upon personal investigation

into the living conditions along Scotts Run in

1933. But the nightmare of poverty on Scotts Run,

which spurred New Deal reformers in the first

place, has faded during the last half-century

of relative prosperity. Nevertheless, the dream

and the nightmare are interdependent, and so,

as a preface to the chapters which follow in this

volume, it is appropriate to reflect briefly on

the historical significance of Scotts Run. The

rapid rise and dramatic fall of King Coal in this

five-mile-long coal hollow located in Monongalia

County, West Virginia, is a case study of how

the unrestrained capitalist development of the

late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

triggered explosive economic growth, on the one

hand, and unrelenting human misery on the other.

Poverty

was not always associated with the Scotts Run

coal field. Coal companies and speculators began

to accumulate mineral rights there in the late-nineteenth

century. However, the transition from an agricultural

to an industrial economy did not make any significant

headway until World War I stimulated the demand

for coal to fuel the national war machine. Monongalia

County produced a mere 57,000 tons of coal in

1899, and only 400,000 tons in 1914, but by 1921,

tonnage soared to nearly 4.4 million tons.(1)

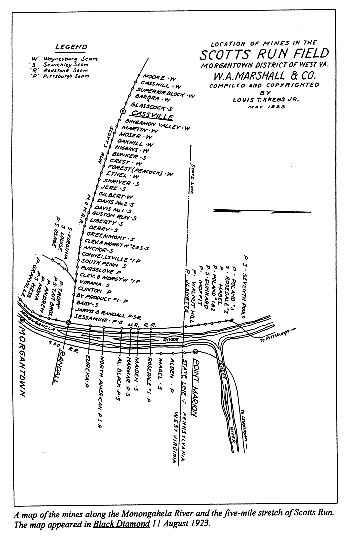

Most of this expansion was attributable to the

development of Scotts Run where, during its peak

years in the mid-1920s, coal companies owned 75

percent of the taxable acres and thirty-six mines

extracted coal from underground. In fact, the

narrow five-mile hollow was one of the most intensively

developed coal districts in the United States,

with a minimum of seventy-three coal companies

in operation between 1917, when the field opened,

and 1942, a period of intense coal company consolidation.(2)

Scotts

Run coal was developed against a background of

unrestrained boosterism. I. C. White, the state

geologist and Morgantown resident, was unabashed

in his writing of the potential for the coal industry

in the Morgantown field. In a 1923 issue of Black

Diamond, a leading coal trade publication, White

observed that in the four commercial coal seams

of Scotts Run, located on the west side of the

Monongahela River across from Morgantown, were

found twenty-five feet of coal; on the east side

of the river were another four seams of fifteen

feet, totaling forty feet of coal. "These

eight seams of minable commercial coal, all being

operated from Morgantown as a center, give this

favored region the unique distinction of having

more coal in its immediate vicinity than any other

city of the world," White proclaimed.

How

is it possible to exaggerate the wonderfully

prosperous future that unfolds itself in the

horoscope of Morgantown.... What the future

has in store for this remarkable coal field

remains to be seen. It has made history in the

coal industry since the day it was opened.(3)

This

was more than mere boosterism, however, for Black

Diamond informed its subscribers in that same

year that "in no section of West Virginia's

many mining districts has the development of a

coal field been more phenomenal than in the history

of Scotts Run."

While

boosterism helped, it does not fully explain the

rapid development of Scotts Run. There were several

important strands of economic reality which converged

at this moment in this previously obscure rural

hollow. Most importantly, geology determined that

Scotts Run would be the place that provided easy

entry into the Pittsburgh seam, considered by

many experts to be the most valuable mineral deposit

in the world. At Scotts Run, the seam was exposed

at 170 feet above the Monongahela River. The Sewickley

seam, located about ninety feet above the Pittsburgh,

was considered the best quality locomotive coal

in the nation.(4) While less economically important,

two other minable seams added to the value of

coal properties along the run.

Nature

played an important role in capturing the attention

of coal producers, but World War I unleashed the

pivotal chain of human events which made development

possible. Coal prices in the national market doubled

under wartime stimulation, and it is significant

that the first commercial mine on the run dates

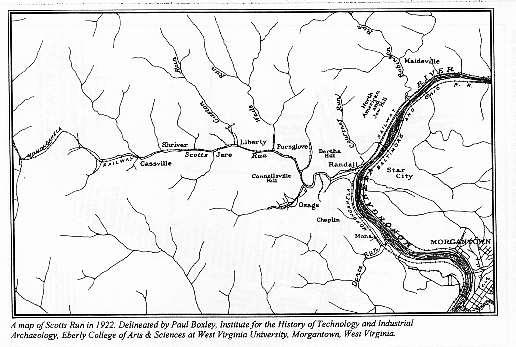

from 1917. Transportation was another key factor.

Scotts Run flows into the Monongahela River, which

already carried more freight originating along

its banks than any other.river in the hemisphere.(5)

With

the rapid development of railroads, the transportation

infrastructure for shipping coal to market was

in place. In 1910, the Morgantown and Dunkard

Valley Railway, an electric trolley line, was

completed from Morgantown to the mouth of Scotts

Run, and up the run to Cassville in 1911.(6) The

Morgantown and Wheeling Railway took over the

line in 1913 with plans to complete the line to

Blacksville, in the western part of the county,

to connect with steam trains, and then to continue

on to Wheeling. The following year, the Buckhannon

and Northern Railroad, built south from Brownsville,

Pennsylvania, connected with the Morgantown and

Wheeling at Randall at the confluence of the run

and the Monongahela River. Between 1915 and 1925,

and after a complicated financial history, these

various lines were purchased by the Monongahela

Railway. In 1921, 175 coal cars per day originated

from Scotts Run mines and were transported over

two sets of double tracks; by 1924, that number

had reached an average of two hundred cars a day

and the markets reportedly were slow.(7)

Finally,

Morgantown, whose businessmen were deeply engaged

in Scotts Run, was a full-fledged service center

for industrial development. The Monongalia County

seat, Morgantown had a well established and diversified

business community serving 16,000 people in the

early 1920s. Moreover, it was the hub of an emerging

transportation nexus of road, river, and railroad

traffic with power plants to supply electricity

for coal mines. According to I. C. White, however,

the greatest advantage offered by Morgantown was

the proximity of six excellent banks which helped

to finance the development of Scotts Run and assisted

in "the growth of Morgantown as the greatest

coal center in northern West Virginia."(8)

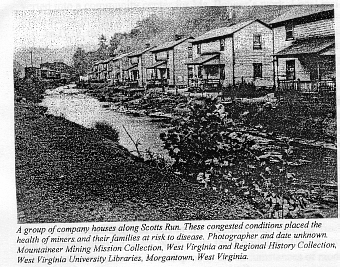

One of the most significant and unique features

of development along Scotts Run was its density.

Generally, developers leased their coal lands

by the acre, but on the run they leased both by

the acre and by the seam. As a result, two operations

standing side by side might be mining two different

seams, a practice which encouraged the multiplication

of coal companies with access to these rich seams

in a very confined space, and which subsequently

would have dire social and economic consequences.

The potential for legal conflicts, and danger

to working miners, is illustrated in the unusual

suit brought to court in 1924 by Chaplin Collieries,

which mined the Sewickley seam above the Pittsburgh

seam being mined by Pursglove Coal Mining Company.

Chaplin charged Pursglove with operating the mine

in a manner which threatened Chaplin's mine and

the safety of his employees. The court apparently

agreed and ordered Pursglove to change his method

of mining in order to protect Chaplin's operation

in the Sewickley seam. Black Diamond, which carried

a regular weekly column on coal news from Monongalia

County, observed that "practically all of

the land in Cass district in the coal belt has

both Sewickley and Pittsburgh coal under it and

in most instances the veins are owned by different

parties."(9)

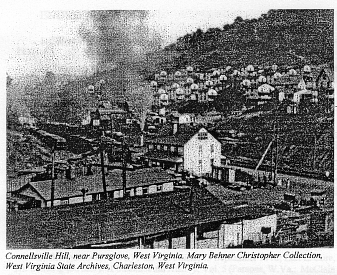

Rapid

industrial development on Scotts Run brought an

equally profound social transformation to this

rural hollow as mining replaced farming as the

chief means of earning a livelihood along the

run. Farmers and farm laborers comprised 66 percent

of the heads of household in Cass District in

1880 and mining only 2 percent; by 1920, coal

mining was 63 percent and farming had declined

to 21 percent. What this meant to people who had

lived there for generations is suggested by an

item published in a 1923 issue of Black Diamond,

which described Cassville as:

…a

sleepy little village that has been there for

years. Its residents do not yet comprehend what

has taken place in their little community to transform

it into a great hive of industry, with rows of

dwellings, stores, schools, churches, power houses,

generating stations, and tipples that lie in an

almost unbroken line for five miles.(10)

As in southern West Virginia, coal development

on Scotts Run required more workers than the local

labor market could supply. Therefore, companies

imported foreign-born immigrants and African-Americans

from the South and thereby precipitated a rapid

increase in the population. An exact calculation

of the population inot possible because the run

is a geographical rather than political sub-division

of Cass District, and the censuses do not always

indicate the exact location of residents. Also,

the decennial censuses for 1920 and 1930 did not

record the surge in population which peaked during

the 1 920s at about four thousand.(11)

Nor is it likely that census-takers differed in

this case in their reluctance to search out coal

camps hidden from view or considered "too

tough" for the census-takers to enter. Moreover,

although the actual number of workers who commuted

to jobs at Scotts Run mines is unknown, a significant

proportion of the work force fell into that category.

Mirroring the pattern reflected in other West

Virginia coal fields, and indeed the American

coal fields generally, the importation of workers

also resulted in a racially and ethnically diverse

population. In fact, one of the distinguishing

characteristics of the population of Scotts Run

during the boom years was the diversity of its

composition. The 1920 manuscript census identified

the following foreign-born ethnic nationalities

among the adult (voting age) residents of Scotts

Run: Austrian, Bohemian, Canadian, Croatian, English,

Finnish, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Irish, Lithuanian,

Polish, Romanian, Russian, Scottish, Serbian,

Slovenian, Ukrainian, and Welsh. Approximately

60 percent of the population were foreign-born,

93 percent of whom were either southern or eastern

European, with native whites and blacks divided

about equally at 20 percent for each group.(12)

The

year 1923 was a momentous watershed in the Scotts

Run coal industry. That year was probably the

high-water mark in production at 4.4 million tons,

but it also was the beginning of a downward spiral

which ultimately led to the depopulation of this

hollow community. The boom lifted the run to prominence

in coal production, but it lasted only seven years

before larger social and economic forces reversed

the process. The "war to make the world safe

for democracy" ended in 1919, and with it

government regulation of the industry. In order

to maintain war production, a government brokered

agreement between industry and labor recognized

the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) as the

miners' agent, but that grudging compromise was

retracted by industry after the war.(13) In northern

West Virginia, coal operators adhered to a non-union

policy prior to the war, and after the armistice

was signed, they awaited their opportunity to

return to the status quo antebellum. One obstacle

blocking their immediate return to prewar conditions

in the Fairmont Field was the fact that C. W.

Watson of Consolidation Coal Company, the dominant

producer in the region, had recognized the union

in 1918 in hopes of carrying the miners' votes

during his campaign for the U. S. Senate. Watson

failed in that quest, but he was forced to accept

the union until there was an appropriate pretext

for rejoining his non-union colleagues. That pretext

came in 1922. By then, the war-heated demand for

coal had cooled significantly, and President Warren

G. Harding lifted federal regulation of the industry,

thus opening the way for an "open shop"

drive by the coal producers.(14) In 1923, officers

of the UMWA and the Central Competitive Field

fashioned, and then early in 1924, signed the

Jacksonville Agreement which maintained the 1922

wage scale Shortly thereafter, the Northern West

Virginia Coal Operators' Association met with

UMWA representatives in Baltimore and ratified

the national accord. Both contracts were to last

until 1927.(15)

In West Virginia, the Fairmont field operators

were alone among the state's coal operators in

signing the agreement, convinced that their companies

could compete with non-union labor in the southern

West Virginia fields. They were wrong, and as

coal prices plummeted to their lowest level in

the market, the northern operators abrogated the

Jacksonville/Baltimore Agreement, thereby precipitating

a seven-year coal war in northern West Virginia.

This disastrous series of strikes and lockouts

lasted from 1924 until 1931. The northern West

Virginia mine war was the longest strike in the

state's colorful industrial history, and it cast

the miners and their families into destitution

and misery, and many of the operators into bankruptcy.'

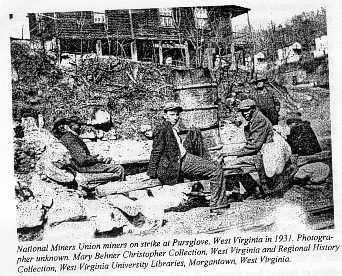

In

1928, with the UMWA in ruin, President John L.

Lewis granted the districts the power to negotiate

their own separate contracts. This left the door

open for the National Miners Union (NMU), a stalking

horse for the Communist Party, to organize the

miners. Under the NMU banner, Scotts Run miners

went out on strike in 1931 against further wage

cuts that already sagged below subsistence levels.

An American Red Cross report called this strike

"the most peculiar strike in history"

because it was directed against consumers who

paid too little to sustain a living wage, rather

than against the operators. After a month's stoppage,

the Scotts Run operators recognized the UMWA,

presumably rather than risk legitimizing the NMU,

a strategy followed by operators in the adjacent

southwestern Pennsylvania coal fields, and the

long, bitter, and frequently violent strike came

to an end. The strike settlement proved to be

the beginning of the UMWA's resurgence. The end

of the seven-year coal war did not bring a return

to prosperity, however, for by 1931, the Great

Depression also had tightened its hold on Scotts

Run miners, many of whom had been without real

work for years. Thus weakened, the economic landslide

fell on them with a merciless fury that drove

most of them into abject poverty.

It

was in this pitiful condition that Scotts Run

became America's symbol of the Depression in the

coal fields and set a new standard for measuring

human suffering in the country which saw itself

as "the last best hope of man." To what

degree life was worse here than in other coal

hollows is difficult to determine, but there was

plenty of misery to go around. Ironically, Scotts

Run received much more attention than other depressed

coal communities because it was far more accessible

to outside photographers, reporters, social workers,

and government agencies.

This

begs the question of just how "isolated"

Scotts Run actually was in the 1920s and 1930s,

a perspective tightly linked to its public identity.

It should be noted that the run was easily accessible

by bus, auto, trolley, or train during this period,

and it was only a few miles from the county seat

of Morgantown. The commercial center of the county,

Morgantown itself was linked into the national

transportation network which connected the hinterland

with major metropolitan centers. Even though outside

observers usually portrayed Scotts Run as "isolated,"

its spatial relationship to the rest of the world

is more accurately understood as "stranded,"

a term frequently employed by contemporary relief

workers to describe the condition of people trapped

on economic desert islands and powerless to alter

their condition. Most of the people were trapped

not by geography, but by the lack of resources,

employment options, and by their culture--many

could not speak English and had customs which

imposed a social distance between them and native-born

residents. A significant percentage were African-Americans,

and racism must be added to culture as an explanation

of why many were stranded" on Scotts Run.

Undoubtedly,

the personal attention of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt

did more than anything else to focus national

attention on Scotts Run. Lorena Hickok, Eleanor

Roosevelt's personal confidante and emissary,

was sent into the Pennsylvania and West Virginia

coal fields on a fact-finding mission in 1933,

and was escorted by Morgantown relief workers

to Scotts Run. There she "came upon a gutter

along a village street filled with stagnant, filthy

water used for drinking, cooking, washing, and

everything else imaginable by the inhabitants

of ramshackle cabins that most Americans would

not have considered fit for pigs," she reported

to Harry L. Hopkins. "Within these shacks,

every night children went to sleep hungry, on

piles of bug-infested rags spread on the floor."

Lorena

Hickok's cry of despair promptly brought Eleanor

Roosevelt for a personal examination of conditions

in the mine camps near Morgantown, and she too

was appalled by conditions on Scotts Run. In her

autobiography, Mrs. Roosevelt related a story

similar to that reported by Hickok regarding the

unsanitary condition of the water supply. "The

Run in Jere, like all the others that, ran down

the gullies to the larger, main stream,"

she observed, "was the only sewage disposal

system that existed. At the bottom of the hill

there was a spigot from which everyone drew water.

The children played in the stream and the filth

was indescribable."(20 ) Another experience

which distressed her occurred in a company house

where a man showed the First Lady his weekly pay

slips. After the usual deductions for rent and

the company store, he was left with less than

one dollar per week to feed his six children.

"I noticed a bowl on the table filled with

scraps, the kind that you or I might give to a

dog," Mrs. Roosevelt wrote, "and I saw

children, evidently looking for their noon-day

meal, take a handful out of that bowl and go out

munching. That was all they had to eat."

Eleanor took many people to see Jere, "for

it was a good example of what absentee ownership

could do as far as human beings were concerned."

These

interrelated themes of paralyzing poverty, unsanitary

living conditions, absentee ownership, and corollary

problems such as poor education, were taken up

during the 1930s by reporters for national publications,

who detailed a prose picture of Scotts Run as

the symbol of the destitution to be found in the

coal fields. One article, in particular, has been

referred to so many times since 1935 when it was

published by the Atlantic Monthly that the phrase

"the damnedest cesspool of human misery I

have ever seen in America" has become synonymous

with Scotts Run.(22)

Even

before Mrs. Roosevelt threw her considerable influence

behind the struggle to improve living conditions

on the run, others had long been busy in that

same enterprise. The Coal Relief Campaign of the

American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) was

already on the scene when Mrs. Roosevelt called

Clarence E. Pickett, executive secretary of the

AFSC, about inspecting conditions in the coal

fields first hand. Pickett and Alice O. Davis,

director of the Morgantown district, met with

Mrs. Roosevelt and helped to establish the itinerary

which brought her to the county and Scotts Run.

With her came the inevitable corps of newspaper

reporters, soon followed by some of America's

most famous photographers, such as Lewis Hine,

Walker Evans, Marion Post Walcott, and Ben Shahn:

Their photographs captured the human face of the

Depression and I provided the visual images which

confirmed the written text. They heightened the

nation's consciousness about Scotts Run, and while

it became easier for social agencies to justify

their work and to raise scarce resources for the

relief effort, the symbol also became a fixture

in the iconography of the public imagination.

The

American Friends Service Committee, and the various

federal relief agencies, brought a strong presence

to Scotts Run, but it would be a mistake to interpret

the appearance of these national organizations

as the first demonstration of concern for the

plight of these stranded miners and their families.

In fact, local agencies, particularly the Council

of Social Agencies and the County Welfare Board,

had been struggling for years to improve the human

condition on Scotts Run. The burden simply had

proven too great for local agencies alone, and

Monongalia County was virtually bankrupt. A National

Red Cross report on Monongalia County for 1931

outlines the scale of the problem confronting

local relief agencies. Of the 50,000 people in

the county, 16,000 lived in Morgantown, 15,000

lived in the coal mining sections, and 20,000

lived in the rural farm sections. According to

the report, "a vast amount of miner's [sic]

children are being fed by charitable organizations."

A nutritional survey undertaken in the mining

sections revealed that in "some instances

as high as 40 percent of the children were found

to be suffering from malnutrition with an average

of 26 percent. Quite a few of the children are

without sufficient clothing and shoes." Compounding

the problem was the closure of every bank in the

county. According to the Red Cross report for

1931, "the county funds have been tied up

in the closed banks and it looks as if tax collections

for the fiscal year are going to be considerably

short." (23)

The problem of tax revenues became even worse

in 1933 after the Tax Limitation Amendment of

1932 was passed, which reduced and limited property

taxes.24 This left much of the relief effort to

private agencies, such as the American Friends

Service Committee, which served 128,692 meals

to children in the mine camps of Monongalia County

between the Septembers-of 1931 and 1932. One half

of its twenty-four feeding stations in Monongalia

County were located in the Scotts Run area, and

by far the largest majority of meals were served

there.(25)

The

earliest, and most personalized, local relief

efforts drew their inspiration from the Bible

School Movement and the Settlement House Movement.

The Bible School Movement depended on trained

lay-workers and volunteers to teach the principles

of Christianity to the "religiously needy"

but gave primary attention to the children. Most

ofthe workers were young women who followed this

avenue to leadership roles unavailable to them

within the conventional structure of the church.(26)

Young women also played a major role in the Settlement

House Movement, the best known example being Jane

Addarns's Hull House in Chicago. Settlement houses

attempted to assist in the "Americanization"

of newly arrived immigrants by promoting English

literacy, citizenship, hygiene, and other basic

adaptive social and life skills. (27)

The goals of both movements converged on Scotts

Run during the 1920s, when Methodist and Presbyterian

churches in Morgantown expanded their work among

the mining families on the run. The Scotts Run

Settlement House began in 1922 when the Women's

Home Missionary Society of Wesley Methodist Church

established a Bible school for children under

the direction of Deaconess Edna L. Muir and Pearl

E. Shriver. In addition to Bible school and Sunday

school, the settlement house gradually expanded

its program to include classes on naturalization,

cooking, motherhood, and other life skills. A

permanent building for the settlement house in

Osage was completed in 1927 and continues to this

day to offer assistance to those in need.(28)

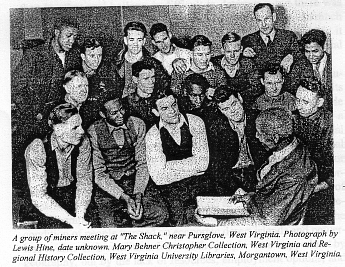

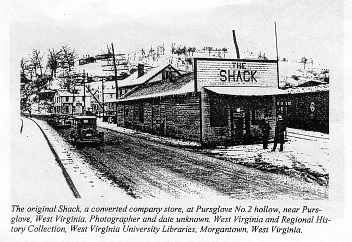

The

Morgantown First Presbyterian Church also sent

a Christian worker, Mary Behner, to establish

a missionary project on Scotts Run. Ms. Behner

began her work at Pursglove in 1928, almost exactly

one year after the Methodist Settlement House

was completed. Programs similar to those at the

settlement house were initiated in a local school,

but in 1931, a mine building was converted into

a community center for Ms. Behner's work. Local

residents called it "The Shack," and

the name stuck.(29)

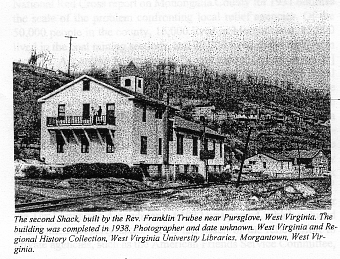

In

1938, the Reverend Franlclin Trubee, the first

ordained Presbyterian missionary to be stationed

on Scotts Run, became the director of The Shack.

He built a new and larger Shack and readily adopted

the methods and philosophical approach of the

American Friends Service Committee, developing

local leadership, and promoting rehabilitation

(helping people to help themselves) through cooperative

exchanges of labor and goods. The unemployed needed

no cash when they participated in the Scotts Run

Reciprocal Economy, The Shack's cooperative. Most

residents could not practice supplemental farming

or extensive gardening as they did elsewhere in

the coal fields because acrid fumes from the smoldering

"gob" piles killed all the vegetation

in the hollow, and congestion from over-development

precluded other uses of the land. However, through

the co-op they exchanged their labor for produce

raised in the hilltop community gardens or for

reconditioned clothing from the recycled clothing

shop. Now in its third building, The Shack, like

the settlement house, has adapted to the circumstances

of modern life and continues to serve people in

need.(30)

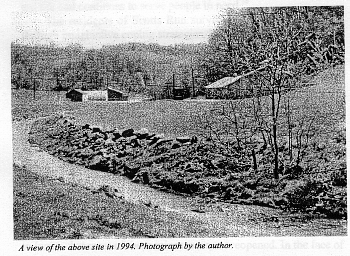

The

residents of Scotts Run survived the Great Depression

through imaginative coping strategies, but the

1930s marks the beginning of a long slide into

historical obscurity for this once teeming hollow.

A number of explanations account for Scotts Run's

short life and slow agonizing decline. The Great

Depression, of course, was a national calamity,

and Scotts Run residents probably suffered more

than most Americans from the debilitating effects

of unemployment, ignorance, ethnic and racial

prejudice, and the other manifestations of abject

poverty. Many left the area in search of a better

life. As elsewhere in rural America, World War

II took many of the young men from Scotts Run,

and after the war they found little incentive

to return.(31)

Technological

change also played a role in the decline of Scotts

Run. The development of diesel engines for locomotives

eliminated a major source of demand for Scotts

Run's famous steam coal, and the rapid loss of

market share to other sources of energy also helped

to insure that most of these mines were not reopened.

In the face of these market changes, the entire

mining industry began a long process of restructuring.

By the 1950s, the numerous coal tracts on the

run had been consolidated into a few large parcels,

most notably those controlled by Consolidation

Coal Company. Mechanization of the mines took

a heavy toll on the labor force everywhere, and

Scotts Run was no exception. With little chance

of employment, miners and their families moved

elsewhere in search of a better life. Their departure

was facilitated by the construction of better

roads and by the widespread ownership of automobiles

after World War II. Finally, the construction

of Interstate 79, which was opened in Monongalia

County in 1974, displaced many residents where

it wrapped around Connellsville Hill, dissecting

Scotts Run between Pursglove and Liberty.(32)

There

was one additional reason for the decline of Scotts

Run: the federal government resettled hundreds

of the native-born white, and most assimilated,

residents. According to one authority, Eleanor

Roosevelt could not solve all of the problems

she found in the coal fields, "but because

she had actually seen Scotts Run" the First

Lady felt compelled to do "something more."

Something more resulted in the conception and

construction of Arthurdale, in nearby rural Preston

County.

Arthurdale

was the first of approximately 99 experimental

communities established by federal agencies to

relocate redundant industrial workers from the

squalor of slums into the more forgiving rural

countryside. The first lady described the desperation

she found on Scotts Run so compellingly that President

Roosevelt ordered his aide, Louis Howe, to cut

through the red tape and purchase the two thousand

acres of farmland for the resettlement community

that Mrs. Roosevelt had in mind. In the end, 165

families moved to Arthurdale, two-thirds of which

originated from Scotts Run.(33)

Arthurdale

represented a uniquely American response to a

social problem, and much of the community spirit

still resonates sixty years later as testimony

to the power of the original dream. Scotts Run

was unique too, but in the public imagination,

it represents the dark side of the American Dream

captured forever in haunting photographs, icons

of the human misery wrought by the Great Depression

in the coal fields.

ENDNOTES

I.

"West Virginia Output Shows Decrease,"

BlackDiamond 68 (28 January 1922): 85.

2.

"Wonder Coal Field of West Virginia,"

Black Diamond 71 (11 August 1923): 180-181; "Sewickley

Coal is Premier Steam Fuel," BlackDiamond71

(11 August 1923): 185.

3.

I. C. White, "Morgantown's Wealth of Fuel,"

Black Diamond 71 (11 August 1923): 178-179.

4.

Howard N. Eavenson, The First Century and a Quarter

of the American Coal Industry (Pittsburgh: By

the Author, 1942), 418; West Virginia Geological

Survey, Characteristics of Mineable Coals of West

Virginia, Vol. 8, A. J. W. Headlee and J. P. Nolting,

Jr., eds. (Morgantown, W. Va.: West Virginia Geological

Survey, 1940), 9-10; Phil Ross, "The Scotts

Run Coalfield from the Great War to the Great

Depression: A Study in Overdevelopment,"

West Virginia History, 53 (1994): 22.

5.

White, "Morgantown's Wealth of Fuel,"

178-179; A. B. Brooks, Forestry and Wood lndustries,

Vol. 5 (Morgantown, W.Va.: West Virginia Geological

Survey, 1911), 28.

6.

Morgantown (W. Va.) Post-Chronicle, 15 September

1910; Earl L. Core, The Monongalia Story: A Bicentennial

History, Vol. 5 (Parsons, W.Va.: McClain Printing

Company, 1982),386, 400-401. On the subject of

transportation, I have been guided by Billy Joe

Peyton, "Transportation Nexus on Scotts Run,"

unpub. Seminar paper, 1993.

7.

Morgantown (W. Va.)Dominion-News,12 December 1971;

Morgantown (W.Va) Post, 19 September 1972, and

18 December 1972; Earl L. Core, Chronicles of

Core (Parsons, WV: McClain Printing Company, 1975),

192; Morgantown (W. Va.) Post, I November 1921;

Black Diamond 72 (15 March 1924): 315.

8.

White, "Morgantown's Wealth of Fuel,"

179.

9.

"Suit Held Vital One," Black Diamond

72 (8 March 1924): 273; "Denies Endangering

Sewickley Seam," Black Diamond 72 (24 May

1924): 619.

10.

Matthew Yeager, "Scotts Run: A Community

in Transition," West Virginia History 53

(1994): 14; U. S. Census of Population; The quotation

is from "Sewickley Coal is Premier Steam

Fuel," Black Diamond 71 (11 August 1923):

185.

11.

1920 Manuscript Census, Cass District, Monongalia

County, West Virginia.

12.

Ibid.; "Report of Missionary Survey in Scotts

Run, W.Va,," Scotts Run Community Center,

A & M 652, West Virginia and Regional History

Collection, West Virginia University, Morgantown,

W.Va. (hereafter WVRHC).

13.

James P. Johnson, The Politics of Soft Coal: The

Bituminous Industry from World War I through the

New Deal (Urbana: University of Illinois Press,

1979).

14.

Michael E. Workman, "The Fairmont Coal Field,"

in Michael E. Workman, Paul Salstrom, and Philip

W. Ross, Northern West Virginia Coal Fields: Historical

Context, Technical Report No.10 (Morgantown, W.Va.:

Institute for the History of Technology and Industrial

Archaeology, 1994): 36; Coal Age 21 (29 June 1922),

1099.

I5.

Workman, et al, "The Fairmont Coal Field,"

36.

16.

Ibid.,36-37.

17.

George E. Smith to Walter Davidson, 22 May 1931,

Records of the American National Red Cross, 1917-1934,

File 868, Box 701, RG 200, National Archiives

(hereafter NA).[Thanks to Sandra Barney for this

item].

18.

Linda Nyden, "Black Miners in Western Pennsylvania,1925-1931:

The National/Miners Union and the United Mine

Workers of America," Science and Society

41 (Spring 1977) For strike conditions and the

NMU on Scotts Run, see Stephen Edward Haid Arthurdale:

An Experiment in Community Planning, 1933-1947,

West Virginia University, 1975), Chapter 1.

19.

Doris Faber, The Life of Lorena Hickok (New York:

William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1980), 143-144.

20.

Eleanor Roosevelt, This I Remember (New York:

Harper & Row Publishers - 949), 129.

21.

Ibid., 126-129.

22.

William E. Brooks, "Arthurdale--A New Chance,"

Atlantic Monthly

155 (February 1935), 199.

23.

Narrative Report, April-October 1931, Records

of the American National Red Cross, 1917- 1934,

File 1310, Box 73, RG 90, NA. [Thanks to Sandra

Barney for this item]. For health conditions on

Scotts Run, see Sandra Barney, "Health Services

in a Stranded Coal Community: Scotts Run, 1920-1947,"

West Virginia History 53 (1994): 43-55.

24.

Charles H. Ambler, A History of Education in West

Virginia from Early Colonial Times to 1949 (Huntington,

W.Va.: Standard Printing & Publishing Company,

1951), 607-609.

25.

American Friends Service Committee, Report of

the Child Relief Work in the Bituminous Coal Fields,

September 1, 1931 - August 31, 1932 (Philadelphia:

AFSC, 1932), 27.

26.

Marcia Clark Myers, "Presbyterian Home Mission

in Appalachia: A Feminine Enterprise," American

Presbyterians 71 (Winter 1993): 253-264. For the

Bible School Movement, see Virginia Lieson Brereton,

Training God 's Army: The American Bible School,

1880-1940 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press,

1990).

27.

For the best contemporary account of the urban

settlement house movement, see Jane Addams, Twenty

Years at Hull-House (New York: The McMillan Company,1910).

For the best modern assessment of the movement,

see Allen F. Davis, American Heroine: The Life

and Legend of Jane Addams (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1973).

28.

Edna Leona Muir, "Scotts Run Settlement Work,"

n.d., and Lena Brookover Barker, "The History

of Scotts Run Settlement House," Autumn 1938,

both in the Settlement House Collection, WVRHC.

Pearl E. was the wife of Frank C. Shriver, president

and General Manager of the Monogahela Supply Company

in Morgantown. Morgantown City Directory 1927-1928,

WVRHC.

29.

Scotts Run Scrapbook, WVRHC; Bettijane Burger,

"Mary Elizabeth Behner Christopher, 1906-

," in Missing Chapters 11: West Virginia

Women in History (Charleston, W.Va.: West Virginia

Women's Commission, 1986), 51; See also, Christine

M. Kreiser, "'I Wonder Whom God Will Hold

Responsible?' Mary Behner and the Presbyterian

Mission on Scotts Run," West Virginia History

53 (1994): 61-92.

30.

"'Why Don't You Bake Bread?' Franklin Trubee

and the Scotts Run Reciprocal Economy," interview

by Ronald L. Lewis, Goldenseal 15(Spring 1989):

34-41.

31.

For an example of this process, see the autobiography

of a former Osage resident, Sidney D. Lee, And

the Trees Cried (By the Author, 1991).

32.

Earl L. Core, The Monongalia Story: A Bicentennial

History, Vol. 5 (Parsons, W.Va.: McClain Printing

Company, 1984), 479-480.

33.

Haid, "Arthurdale," 68-70; Faber, The

Life of Lorena Hickok, 146.

Return

to History of the Area |